HYPOTHESIS: Education in the 21st century faces many serious issues and challenges. Simply because it is one of few instruments we still have that can significantly contribute to solving problems of this planet and society. The question is how education should be shaped to make the most of its potential?

The idea of the article was born last school year, during my CLIL project called Why is the River Váh Called “Váh”. While I was unfolding the geography and history of the river in English with the thirteen years-olds, I was considering the relation of assignment and students’ outcomes. If the focus of teaching was not only on gaining a set of knowledge and storing it in students’ memory, learning results would be worthwile, more deep-drawn and effective.

This article is based on my expertise and practical experience. It aims to inspire the changes in educational practices to make learning more sound for the life in this century. The main topic discussed below is the potential of learning outcomes for making a positive difference.

THE STORY ABOUT MEETING THE “REAL” OUTCOMES: I got inspiration from my friend, Dr. Flavio Pinto, who is a scentist. His work comprises of translating from Sanskrit, describing and explaining the figurative language, archaeological findings, historical artefacts and toponyms. As I was browsing through his papers on academia.edu, one of them attracted me immediately by its title: The rivers Váh and Nitra. Two examples of Sanskrit names of rivers in the heart of Europe. I grew up on the river Váh, my hometown has the word Váh in its name: Nové Mesto nad Váhom. I realized that I actually have no idea why is that river called “Váh”? In other words – what does the word “Váh” mean? It seems to have no meaning in my language at all. The Sanskrit origin of the word unfolded a series of meanings and Dr. Pinto came up with very interesting information about the life on the river Váh in the past, may be at the times, when Sanskrit was being used in this geographical area by common people. It was the information I had never heard before. The information was only one dimension of the paper. The higher level dimension was the main message that one could read between the lines: Our ancestors considerd the river a deity. They fully appreciated that the river was of a vital importance for them and this fact determined their behaviour towards Váh: worship and protection. (Pinto, 2022) We have forgotten about what does the river mean for our lives. Our generation takes it for granted. This fact determines the behaviour, which causes serious damage and pollution to the river and to the life in it. The appreciation of this fact was a springboard for my follow-up school activities.

My ideas beyond this experience revolved to exploring what my pupils learn about the river and its history at school. Both curriculums of History and Geography contain relevant topics. So I tried to find out directly from the 8th-graders what interesting facts about Váh they learned in History and Geography lessons. The answers were like “nothing” or some general knowledge like the geographical location of the river. One would say: a typical teenagers’ reply. However, I tried to dig deeper and found out that they didn’t understand why were they supposed to know something about Váh? They didn’t find it interesting or useful at all. Pupils often do not see the purpose of learning. They do not know what is the information for, how to use it. In such a case the whole process of learning loses its value.

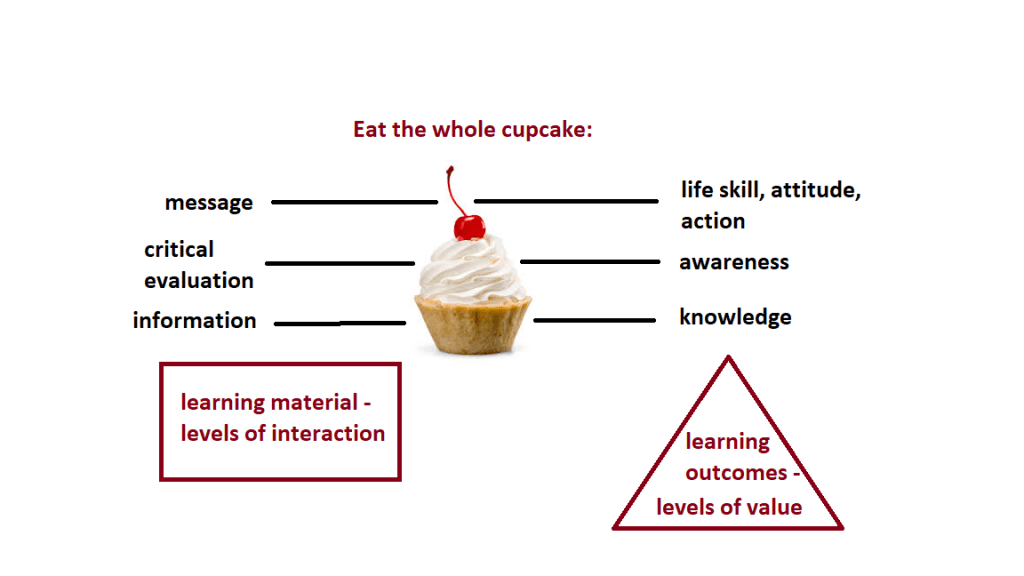

Their learning so far had reached the level of obtained knowledge – information set (Picture 1), that had not been even stored in their memory yet. The value of such learning outcome can be questioned. This is definitely not the result that education should aim for. Students can increase the value of any information gained within a learning process by personal critical evaluation that results in applying it in everyday life. To put it simply, to have students “eat the whole cake”, teaching should aim for outcomes that are usable and valuable. (Picture 1)

I found Flavio Pinto’s paper so worthful that I decided to show it to students at school. The potential of turning this scientific paper into a teaching material consisted in its content coming in several layers: contextualized and interelated information that can: provoke thinking, lead to awareness and grasping the extremely important and valuable message of the paper and thus inspire students and open their minds. (Picture 1)

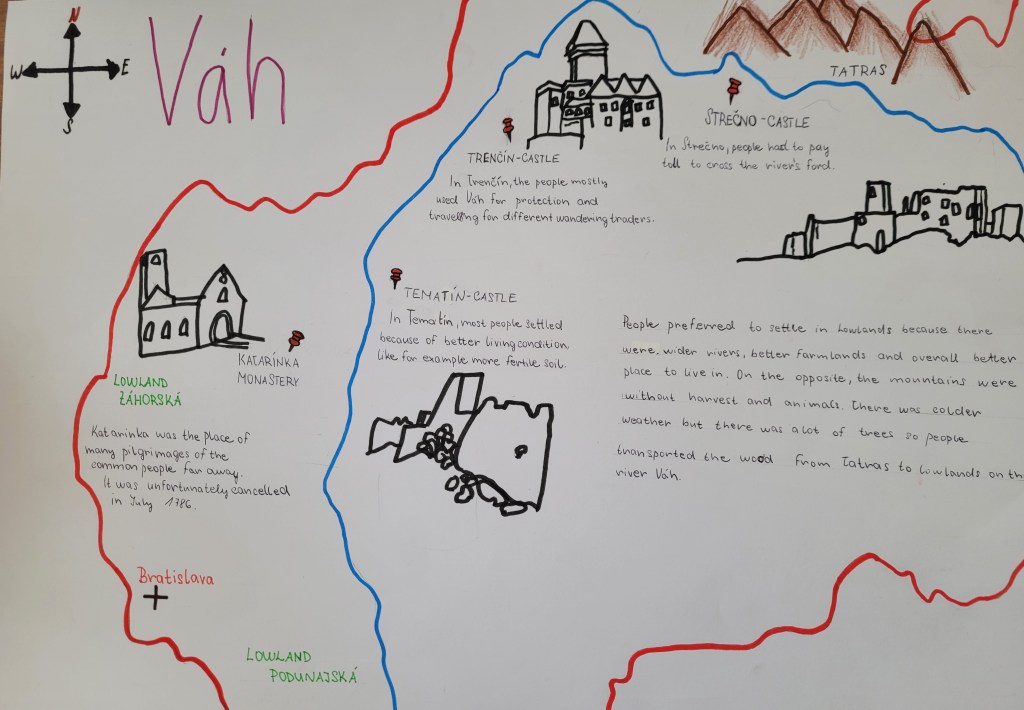

The CLIL1 project started by designing the Geography and History worksheets in English for pupils to guide them through searching the relevant background information. I used scaffollding method. Students were focusing on geographical description of the river, its basin and surrounding. They were also collecting information about the life on the river back in the ancient and medieval times. Various types of resources were mostly about old settlements, hill-forts and monasteries, pilgrimages, old trade routes along the river, about functions of the castles etc.

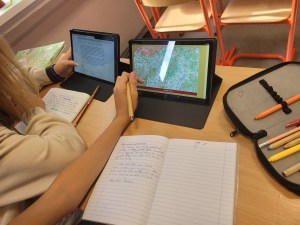

Picture 2

Students had to use their map reading skills to explore geographical features of the river Váh.

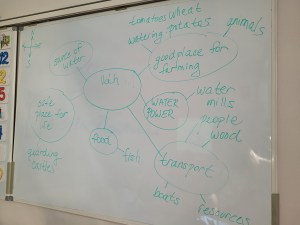

Picture 3

Based on the geographical and historical information they considered different benefits of the river for the life of people in the past.

The important ingredient of students’ work was critical thinking. Collected information had to be evaluated, compared, judged, ranked, categorized and interrelated. For example, children found out that unlike today, there were no bridges in the past. And the question was what impact it had on people’s everyday life, how they used to cross the river when necessary? What skills did they need to make it? The students collected the geographical information about the northern and southern basin of Váh. In that stage they were listing and recording the information. (Picture 3) But to get more effective outcomes, the tasks were designed to get more out of it. Students were to compare how the life was different in the northern part of the river from the one in the southern part. How did the two areas communicate together and why? (Picture 4) In this way they came up with new findings, new questions and new logical deductions. All in all they discovered the stories about tolls and forts on the river, about transport of wood and other comodities upstream and downstream, about the reasons why pilgrims wandered along the river etc. They became aware of the fact, that Váh was the main resource. (Picture 3) If there was no river, people wouldn’t have survived there.

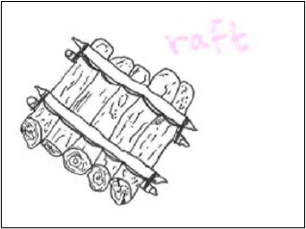

Picture 4.

Students’ illustration. They understand the logic behind the tradition of Slovak wooden rafts, that are nowadays commonly viewed only as a part of our folklore heritage.

The findings, results and information in the form of posters were presented to Dr. Flavio Pinto online and shared with other peers. (Picture 5)

In the next stage of the project Dr. Flavio Pinto prepared his interactive online presentation for students based on Sanskrit translations of the word Váh.

The word /vaha/ in Sanskrit also means “road”, 2“carriage”, “boat” and “knowledge”. The verb /vah/ in Saskrit also means “to flow”, “to transport”, “to carry”, “to go by”, “to go in”, “to swim”, “to pass”, “to lead home”, “to lead towards”, “to guide”. (Pinto, 2022)

At this stage pupils understood for example why rivers are flanked by the roads. Because in the past horses and bulls used to pull the boats upstream. (Picture 6)

Picture 6

The two horses walking along the river bank are pulling the boat with cargo upstream.

The new knowledge for them was also that observing and knownig the river was of a vital importance for people then. They had to measure the water properly before going in to cross it with the animals and carriage.

In Sanskrit the word /vaha/ also means “measure of capacity” (“horse”, “bull”, “draught-animal”) and corresponds to the “shoulder of any draught animal” (“breathing of a cow”). The “name” of the “river” (“measure of capacity”) suggested that the crossing of the “water” of the “river” on a “carriage” was “feasible” if the water was not higher than the “shoulder of the draught animal” so that the “breathing of the animal” was possible. (Pinto, 2022)

An ancient river crossing technique, still in use in the last century by transhumant shepherds, was to have an animal “to pass” the “river” (“finding”, “road”) before the rest of the flock. The testing animal was fixed using a “rope”. If the test-animal – the strong “bull” – could “pass“ the “flowing” “water” and reach the other side of the “river”, then the rest of the flock could go and “pass” safely. In some cases a “lamp” was placed on the “animal’s” “head”. If the “light” remained on and visible in the distance above the “water” (without the water turning it off), then it was safe and feasible to cross the river. (Pinto, 2022)

Picture 7

Crossing the river.

Our ancestors were using different sources of information than people today in order to assess the water and estimate the danger. They were for example listening to water sounds:

The name (Vah) indicated the nature of the water: it contained useful information about the essence of the place – a river in this case. A place name was meant for the reasoning about its “sound” and its “meaning” connected to the “conditions” of the “water” and to the “action” of the “goer”, the “traveller”. This “reasoning” about the “sound of the water” , the “sound” of the “deity” of the “water” was fundamental” for the “motion” of the traveller. (Pinto, 2022)

People were sensitive to different sounds of the river. If it was noisy, for example, the river was wild and dangerous. Students used this information and compared it with how people perceive the river nowadays.

The overall point of the project was to understand and to become aware of how wise our ancestors were, how much they protected and worshiped the river because it was so important to them and considered it a deity.

The “water” was linguistically equated to a “deity“ – in “heaven” as on “Earth” – a “mother” “Goddess” , or a “god“ „father”, the “Supreme Spirit” the “creator” of the “sky” and of the “earth”. In nature water produces sounds. The “water as “Supreme Spirit”, as “deity”, was considered to be able to talk and it was “fundamental” for the “goer” to pay great attention to the “sound” of the “words” of the deity” of the “place”. The “traveller” was a “mortal” “man” who used to meet the “water” “god” along his “road”. The “traveller” had “fear” of being “killed” by the “deity“, the “god” – the “river” “father” – or the “Mother” Goddess”, “Mother” “Nature“. The “words”, “deity”, the “god” of the “water” – just like the “place” “names” – gave the “rules” for the“mortal” “traveller in “motion” along the “road. (Pinto, 2022)

This idea added an environmental dimension to the project and provoked reflection on today’s attitude of humankind to the nature. And this is considered to be a “real” valuable learning oucome in this paper.

ASPECTS OF APPLICATION IN TEACHING PRACTICE: The project was presented to Slovak and Hungarian teachers in Erasmus plus CLIL Methodology course in Alghero, Italy (07/2023). When I saw the teachers’ enthusiasm about the idea, method and concept of the project, I decided to write this article in order to spread the information further. It has to be said at this point that Vah topic is only one example (actually a very good one) of how beneficial it can be for young generation to work with valuable scientific resources, in a way that involves critical thinking and English as a means for working with information. Practical aspects of using CLIL and critical thinking discussed in the following paragraphs are aplicable to any topic and any subject at school.

“Working with information” and critical thinking operations.

It is being widely suggested that one of the most important skills for students to be developed at school is the ability to find and select the right information. This is admittedly true. However, regarding the information, there is one more important aspect: the ability to assess it critically and to use it effectively. Within the project, the students were guided in finding the information and they were focusing on selecting the relevant pieces. The upgrade was the task for them to relate the particular information to another one, to make logical deductions, to compare, analyse and summarise. These operations are more or less of what is meant by “working with the information”. Compared to simple searching, selecting, listing and recording it, these are higher cognitive operations (Segal at al., 1985), that can bring better learning results. To go even further, the next level of “working with information” (in case of the project) is that students: are getting aware of the importance to protect nature, know where the idea comes from, and finally opt for eco-friendly thinking. Such natural understanding can result in their new inner beliefs, attitudes and relevant behaviour. And this is the most important outcome of learning that stands above the obtained language competence, and any subject knowledge.

CLIL method

Content and language integrated learning has many features that make this teaching approach stand out among the others. (Coyle at al., 2010) It brings real life into schools and also the other way round, CLIL connects the school knowledge with real life. Basically, CLIL integrates foreign language with the content of other school subjects. The learned foreign language becomes a live part of everyday life of a student, not olny the school subject which is a must.

In this article I am not going to list the benefits of CLIL for language skills development. There are many researchers who proved CLIL brings significant gains in language proficiency (Coyle at al., 2010). I am going to point out the benefits of CLIL for learning in general.

The great asset of CLIL approach is that it constantly challenges students’ zone of proximal development. The zone of proximal development (ZPD) refers to the difference between what a learner can do individually and what he or she can do with the help and scaffolding from a “more expert” partner. ZPD is the zone where the task is just beyond the individual’s capabilities. To learn, students need to be presented with tasks just out of their ability range. That is the case of CLIL approach. And it is not only the foreign language that makes the tasks challenging. It is also discovery and exploring, problem solving tasks, and project based learning method which are widely used within CLIL approach.

The zone of proximal development was developed by Lev Vygotsky3. The zone of proximal development has been defined as:

“the distance between the actual developmental level as determined by independent problem solving and the level of potential development as determined through problem-solving under adult guidance, or in collaboration with more capable peers”

(Vygotsky, 1978, p. 86).

Scaffolding is a key feature of effective CLIL teaching, in terms of both language and subject aims. The teacher continually adjusts the level of his or her help in response to the learner’s level of performance. This help may come from other learners too. Thus, the use of activities which demand collaboration in order to achieve an outcome – rather than a learner working alone – can be vital for both cognitive and linguistic development. Also Freund’s study (Freund, 1990) shows that children who solve the problem individually perform worse than children who do the same task with the help of others. In wider perspective, Vygotsky views interaction with peers as an effective way of developing skills and strategies.

CLIL method in practice comprises a huge portion of cooperation in its various forms. Cooperation in our society has been replaced by individualism. We call for independence and celebrate personal achievements. This leads to rivalry, competition, stress, loneliness and lack of sense of belonging which is so natural for a humankind.

I know from my teaching practice that it is impossible to do CLIL without cooperation and social interaction. Teachers and students benefit from the opportunity to complement each other, to learn from each other, to help each other and to work in groups or teams. The paradox is that the learning results achieved cooperatively are more valuable for an individual than any individual achievement. The gains are broader not only in terms of knowledge, but also in terms of acquired strategies, attitudes, soft skills and personal qualities.

Cooperation encourages inclusion. It is the essence of it. Inclusion is the way of connecting people together again. This is another great asset of CLIL. Inclusion and cooperation, which are so natural for CLIL, have a great positive impact on learning outcomes.

To include, not exclude, to make diversity an advantage, not a reason for rejection, unhealthy comparisons or hatred.

TO SUM UP the experience with CLIL project based on the scientific paper by Dr. Flavio Pinto showed that critical thinking and CLIL are worth to be a part of modern education. CLIL has every potential to bring the excellent scientific works from archives into real life, and make it work for people. With the right teaching approach students can achieve valuable outcomes. Developing critical thinking, supporting cooperation, creating the inclusive learning environment based on social interactions can make a positive difference in the 21st century society.

Resources:

- PINTO, F.: The rivers Váh and Nitra. Two examples of Sanskrit names of rivers in the heart of Europe. 2022. Dostupné na https://www.academia.edu/79009173/The_names_of_rivers_Vah_and_Nitra

- Segal, J. W., Chipman, S. F., & Glaser, R. (Eds.) (1985). Thinking and Learning Skills. Volume 1: Relating Instruction to Research. Hillsdale, New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- SPADA & LIGHTBOWN (2013): How Languages are Learned, 4th edition. Oxford University Press.

- Coyle, D, et al, (2010), CLIL Content and Language Integrated Learning, Cambridge University Press.

- Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Berk, L., & Winsler, A. (1995). Scaffolding children’s learning: Vygotsky and early childhood learning. Washington, DC: National Association for Education of Young Children.

- Copple, C., & Bredekamp, S. (2009). Developmentally appropriate practice in early childhood programs. Washington, DC: National Association for the Education of Young Children.

- Freund, L. S. (1990). Maternal Regulation of Children’s Problem-solving behavior and Its Impact on Children’s Performance. Child Development, 61, 113-126.

- CLIL (Content and Language Integrated Learning) is a language teaching approach that combines the use of foreign language as a means for learning the content of other school subjects. ↩︎

- Words in quotation marks are the meanings from Sanskrit translations. ↩︎

- The Soviet psychologist and social constructivist (1896 – 1934). ↩︎

Pridaj komentár